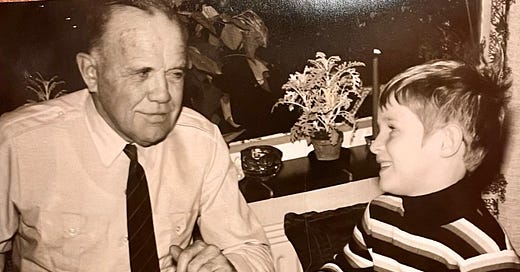

It was the late seventies, one of the many afternoons I spent at the house of my grandparents. We had lunch together, probably the traditional Dutch cheese sandwich, followed by fruits, pear in this case. The three of us were chatting when the phone rang and my grandfather, Piet, got up and picked up the receiver, listened, disconnected and returned to the table quietly. “Jaap is dead” he said and finished his pear. Not a word was spoken. Piet returned to his lounge chair while grandma cleaned up the table. I started toying around with the amateur microscope I had received as a gift. It was silent. I thought I had to cry, but couldn’t. What I did instead was tune in to the profound grief that my grandfather was just experiencing. I felt it go through my entire system and never again have I registered someone else’s pain this astutely. It was if I were him in that very minute and therefore no words were necessary from me. I just knew.

Jaap, born Jacob, was my grandfather’s younger brother. Two boys from relatively humble backgrounds who, born in the early 1900s, managed to build families and careers in the slow but peaceful pre-war years in The Netherlands. A country that stayed out of World War I and believed it would somehow squeeze through when World War II came around, which of course it did not. Gifted and hardworking brothers, two young men who had an enormous future ahead of them, the war suddenly entrapped them. The scene of learning of one of the two passing away was not just defined by one man losing his younger brother to cancer in his early sixties, it was also reflecting on the miracle as to how Jaap had been with us for so long.

Jaap and family and baby daughter were stuck in the Dutch East-Indies - what is now Indonesia - and were all captured and imprisoned by the invading Japanese forces in 1941. A historical event that was left underreported in many ways, colonialism of course evoked negative sentiments in the post-war world. Jaap’s wife and daughter ended up in a concentration camp and managed to somehow survive while enduring the most gruesome treatment. It was only fairly recently I heard the story of how one of the Japanese prison guards who helped the captive women and kids to extra food had his face sliced open by his fellow countrymen in front of the prisoners. While this gives you a taste of the level of cruelty that befell the many Europeans in Japanese camps, worse was reserved for the men who were put to work at the infamous Burma Railway, the horrors of which comprised endless hard work, starvation, torture and in many cases of course an early death. It was a sheer miracle that an emaciated Jaap and his wife and daughter walked out of this tropical hell at the end of the war in 1945 and managed to resume their lives.

My own grandfather, Piet, was equally ensnared but in his case it happened in The Netherlands itself where the Nazis cracked down on the emerging Dutch resistance. This followed the massive strike to protest the first deportation of Jews at the end of February 1941. It was the sheer brutality of that first razzia on the Jonas Daniel Meijer square in Amsterdam that stirred up emotions under the Dutch who started to organize a resistance movement, with a significant role for Piet’s hometown Vlaardingen. Yet the somewhat naive Dutch were no match for the ruthless Nazi machine that was ready to destroy even the slightest indication of disloyalty, let alone an attempt at resistance.

The details remain murky, but lore has it that the nascent resisters were betrayed, another story is that a list naming all members of the resistance team, enthusiastically put together to get organized, somehow fell into German hands. Piet was part of the group and found himself in the infamous ‘Oranje Hotel’, the Dutch prison that the Nazis had confiscated to detain and torture whoever obstructed. Not for long though, on April 1 that year Piet, together with some of the Jews who were captured at the infamous razzia in Amsterdam, were on their way to Buchenwald concentration camp.

As close as I was to by grandfather and how trusting he was of me in return, it would prove to be impossible to permeate the shield that Buchenwald had created around him. A deeply loving man, caring for his family, jovial - he liked a good drink - and successful in business, any inquiry as to what actually transpired in that German hell was met with utter silence. Only once did he share a story about how they were forced to crush rocks at the end of a gruelling labour day, only to be beaten to pulp once it became clear that they had picked up relatively small stones to crush. My grandmother would circulate only a few more stories and these were later corroborated to me by a Dutch historian and writer who had long done research in particular into Buchenwald. But these details never came from Piet. He had made it clear he should not be talking about these or burden me with the horrors that befell him. Was it a coping mechanism, was discussing the trauma a sign of weakness or something so inconvenient to better not be open about?

Piet passed away in 1979 at age seventy-two, not long after Jaap. And like his brother it was cancer that brought a once strong man down. Heavy smoking and drinking were of course attributed as the lead causes and the story of ‘that generation was not as health conscious as ours’ was and is still the widely accepted one. It is remarkable that the traumas that had ultimately turned Piet and Jaap into living wrecks were never really seen as the real causes that might have contributed to their deaths at an age at which in today’s world people only begin to retire. Piet and Jaap were spent forces. I often stayed over at my grandparents’ house and loved it and never wondered about Opa Piet starting the day with a cigar sitting on the side of his bed and finishing the day with an empty cigar box. That’s what they did. Or Jaap blowing though packs and packs of cigarettes a day. Trauma was not a discussion in post-war Netherlands, it was simply not being talked about. Jaap’s favourite brand of cigarettes was more the centre of the actual family debate.

The survivors kept quiet, the family pried a bit, but never attempted to really figure out what happened, what the hurt was, where the actual pain ended up residing. The Dutch recovered and everyone worked his ass off to rebuilt the total mess that the Germans had left behind in 1945. Piet and Jaap were no small part of that and became, like many in their generation, quite successful in the process.

Upon retiring Piet got a boat and I had the privilege to sail with him for many summer days and weeks over the Dutch rivers and into Belgium and Northern France. A good meal every night out, of course with a good drink, and he even let me have an occasional beer, recognizing the emerging teenager I was. Walking back to the boat was always hard for him, the unhealthy lifestyle had taken a definite toll on him.

Piet and Jaap became icons to me and as I grew older and the gruesome stories of World War II became clearer through books and movies, their survival became a testament to the remarkable nature of recovery and overcoming the deepest trauma. Their war was not one of actual fighting, it was one of staring death in the face and defeating it. Their faces, their confidence and icy calm demeanour, always smoking, revealed an unusual and hard to define kind of heroism.

Piet was more than a father for me. I loved him, I respected him and aspired to be him. When he died I was heartbroken and still am as I think of that fateful day following the evening my mother and I were the last ones to see him in the hospital. As we stepped in the funeral cortege a few days later my father remarked that ‘maybe we should have asked him some more about Buchenwald’. Now that we are some thirty-six years after his death I wonder about that question. I don’t really think we needed more Buchenwald stories, however. We actually needed to learn more about Piet’s world and his psyche and the impossibility for him to shake off the trauma that probably defined a large part of his life after the war. That’s what we do today when we encounter the survivors of terror and torture, or when we consider the lives of hostages once they are released. But Piet and Jaap were part of a generation that survived and managed it all in their own way, a journey that in all likelihood accelerated to a much earlier death.

Today that world war ended eighty years ago. Fewer and fewer of those that lived it are still alive. Holocaust survivors, resistance fighters, veterans and ordinary residents who battled hunger and everyday terror. Or the mothers who, like my late grandma, answered my mother asking why her dad was away for so long. “He’s on a business trip” she would say. What did they know? And what do we know, eighty years on? We are still working on it and defining it. One thing is for sure: we will never forget.

Beautifully written piece, thank you.

A very moving memory of a real great grandpa!

Also an important, which we called an ego document in Dutch. that sheds historical and human light on the incredible lives and fates of the Shoah-generation. Indeed, not, never to forget them!